Many water management problems stem from what we describe as the competition, interconnection, and feedback among Natural and Societal processes within a Political Domain (NSPD). Within the natural domain, the interplay among three important variables— water quantity, water quality, and ecosystems — can lead to conflict. Within the societal domain, there are equally complex interdependencies and feedback among social values and cultural norms, assets including economic and human resources, and governance institutions. Our observation that natural and societal domains are linked is not novel. Our argument, however, is that assuming that there are strong boundaries between these domains is likely to get in the way of resolving complex water management problems.

Many water management problems stem from what we describe as the competition, interconnection, and feedback among Natural and Societal processes within a Political Domain (NSPD).

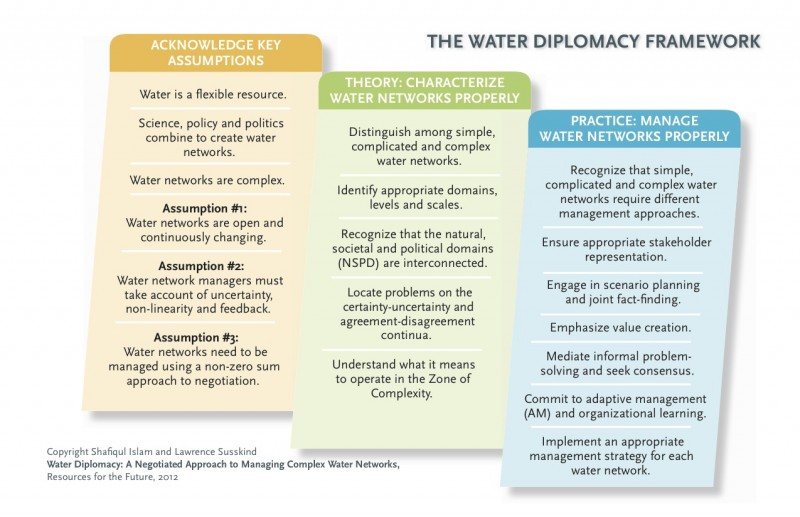

Currently, there is no accepted framework to explain how these domains interact or how these interactions can and should be managed. A key goal of our work has been to create a framework to facilitate production and use of “actionable knowledge” for the characterization and management of complex water networks. Here, we propose a new Water Diplomacy Framework (WDF) rooted in ideas of complexity theory as well as mutual gains approaches to negotiation.

The following table outlines key elements of the WDF and contrasts it with conventional conflict resolution approaches for common pool resources.

The Water Diplomacy Framework |

Conventional Conflict Resolution Theory |

|

|

Domains and Scales

|

Water crosses domain (natural,societal and political) and boundaries at different scales (space, time, jurisdictional, institutional) |

Watershed or river basin within a bounded domain. |

| Water Availability | Embedded water, blue and green water, virtual water, technology sharing and negotiated problem-solving to arrange for re-use can “create flexibility” in water for competing demands. |

Water is a scarce resource and competing demands over fixed availability will lead to conflict, if not war. |

| Water Systems | Water networks are made up of societal and natural elements that are open and cross boundaries, and change constantly in unpredictable ways within a political system. | Water systems are bounded by their natural components; cause-effect relationships are known and can be readily modeled. |

| Water Management |

All stakeholders need to be involved at every decision-making step including problem framing and formulation; heavy investments in experimentation and monitoring are key to adaptive management; the process of collaborative problem solving needs to be professionally facilitated. |

Planning is usually expert driven; scientific analysis often precedes participation by stakeholders; long-range plans guide short-term decisions; the goal is usually optimization given competing political demands. |

| Key Analytic Tools | Stakeholder assessment, joint fact finding, scenario planning and mediated problem-solving | Systems engineering, optimization, game theory, and negotiation support systems |

| Negotiation Theory | The Mutual Gains Approach (MGA) to value creation; multiparty negotiation keyed to coalitional behavior; mediation as informal problem-solving |

Hard bargaining informed by Prisoner’s Dilemma-style game theory; principal-agent theory; decision-analysis (Pareto Optimality); theory of two-level games |